That US economic activity fell sharply in real terms in 1945-46 is beyond question. Industrial output was down as early as April 1945 as the war in Europe neared its end. With Japan's surrender, the War Department cancelled contracts worth nearly $23 billion in August alone, and 2.5 million workers were released from war jobs in the first month of peace. The industrial downturn continued into 1946, and the peak wartime level of manufacturing activity was not reattained until 1950, a reflection of the scale of the country's earlier economic mobilisation.

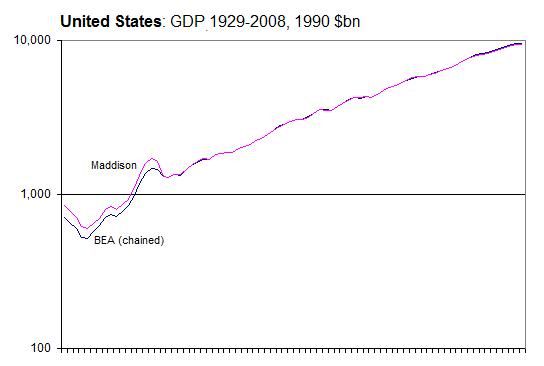

What's at issue is the extent of the drop, both in the US and globally. Maddison's data show the 1990 Geary-Khamis dollar value of US GDP falling from 1.64 trillion in 1945 to little over 1.3trn in 1946. And this decline represents 7% of gross world product in 1945, enough to turn an otherwise small further decline from that year's already greatly reduced aggregate global output into a massive postwar world contraction.

But today's official US historical National Income & Product Accounts show no such calamitous plunge in the first year of peace. The answer comes from the Bureau of Economic Analysis, which in 1996 replaced its fixed-price real GDP estimates with chained indexes incorporating year-on-year price changes. The May 1997 Survey of Current Business explains:

As measured by the old 1987 fixed-weighted index, real GDP dropped 25 percent from 1944 to 1947, reflecting the post-World War II demobilization and the associated sharp cutbacks in defense spending. However, much of this drop reflects the use of 1987 prices for defense equipment rather than the low postwar prices for defense equipment. As measured by the more appropriate price weights of BEA's new chain-type indexes, the postwar drop in real GDP is 13 percent.

Maddison's GDP trend thus corresponds closely to the BEA series abandoned in 1996, with a base-year shift from 1987 to 1990. The effects are significant: in today's chained series, the GDP of 1945 was not equalled until 1950; according to Maddison, this didn't happen until 1953. The higher 1944 wartime peak was surpassed only in 1951 according to the BEA, but in Maddison's series the 1953-54 recession meant this took until 1955.

Nor is the impact in Maddison's data of merely national sugnificance: his series indicates a 7% fall in world output in 1946 alone, equalling that of the previous year when the ending of Allied war production combined with the devastation of German and Japanese industry & infrastructure. Replacing his US trend with the BEA's, however, the global drop is about 3% - far smaller than that of 1945, as we might expect given the ending of the world's largest and most destructive armed conflict.

And the effect isn't limited to the period of victory and postwar adjustment & overseas reconstruction. For Maddison's trend before 1946 broadly coincides with the BEA's. If the chained US series is correct, Maddison's 1929-45 US data are overstated by 10-20% or more relative to those that follow - and the discrepancy widens toward the beginning of the period covered by both sets. Which is doubly problematical, because there's good reason to believe that his figures for earlier years already understate the real US share of GWP.

The current-price data certainly support the chained series as a more appropriate representation of reality. Current-price GDP was virtually unchanged in 1946 (from $223bn to $222.1bn). Durable-goods manufacture was down sharply, almost entirely down to the plunge in output of ships & vehicles; government's share was down by an even greater amount as millions settled back into civilian life. But consumer-goods production was up, as were retail & wholesale trade, construction and services.

Prices were certainly up substantially with the lifting of wartime controls, a trend which would continue in 1947 and 1948. But the scale of Maddison's real-GDP downturn would require a rise of more than a quarter in the unit value of net output. It just isn't there. Consumer price inflation picked up sharply in the second half of 1946, but for the year as a whole averaged little over 8%. Commodity prices rose more strongly, but their greatest increase would come in 1947. The BEA's GDP deflator shows only a 12% rise, the same as that implied by the old 1947-price data. Real GDP therefore fell by 11%, again in line with the 1947 series.

Maddison himself was aware of the issue, admitting candidly that his preference for the 1987/90-price version derived in large part from his doubting a near-doubling of real US GDP in 1937-50. It's an enormous rise, but less daunting when we recall that per capita income in 1937 was still below the level of 1926, and that both his and the chained series indeed show such a doubling for the still briefer period 1937-44. The alternative of a real 25% drop in 1944-47 requires a far greater leap of faith.

If Maddison's 1870-1945 estimates of US GDP are misleading, his world totals cannot but be affected given the size of the US economy even in the late 19th century. Lowering them to conform to his 1946-2008 figures would however indicate an unrealistically low US share of a mere sixth of world output in 1913, when current-price data suggest something nearer to a quarter than Maddison's raw 19%. Adjusting the US series necessitates correcting the data for other parts of the world, some of which already appear overstated.

The 1946 problem should remind us that 1990 G-K dollars can be an unreliable guide in estimating historical GDP. The pricing issues can too easily leave us with implausible trends or relative volumes of output. The Maddison dataset and extrapolations from it should be used with great caution until we can come up with something better.

No comments:

Post a Comment