The paper is essentially an extension to roughly the area of today's Iraq of Elio Lo Cascio and Paolo Malanima's 2009 critique of Angus Maddison's 2003 estimate of per capita GDP (in 1990 dollars) in the Roman Empire by way of the England of 1688. Confused? It gets worse.

The tortured calculations that follow are ultimately down to Maddison, who used Gregory King's estimate of 17th-century English national income as a half-way house in estimating the ratio between modern GDP levels and those of ancient societies. The latter, he concluded, had per capita incomes of around $500, about two-fifths of a 1688 English average equivalent to two tons of wheat.

Lo Cascio & Malanima challenged Maddison's use of average cereal (rather than specifically wheat) prices in the calculation and his reliance on the exceptionally low prices of 1688. England's true wheat-equivalent income, they argued, was nearer 1.2 tons per head - no better than Roman Italy's and less than 50% above that of the Roman Empire generally. Income growth in Europe was thus virtually non-existent over the intervening 1,674 years: other areas of Europe were far behind Italy in Roman times, just as they were far behind England in 1688. So European prosperity may have sagged and revived in the interim, but the net effect was minimal.

In converting Maddison's 1688 grain price denominator to 1676-1700 wheat prices, however, LCM omit to adjust English GDP - the numerator - for the higher 25-year general price level consistant with their revised wheat value. Nor, after questioning Maddison's assumption that Italian GDP per head was 52% higher than the rest of the Empire - whose inhabitants, we are told, could only afford 790kg of wheat - do they incorporate their alternative suggestions of a lower peninsular level. Italian average income may have approached the later English level in terms of wheat: it may equally have been 20-25% lower.

Foldvari & van Leeuwen incorporate LCM's reworking in their approach. What follows is largely guesswork founded on Makis Aperghis's estimate of the value of agricultural production - here rounded from 7,500-10,500 to 10,000 talents, from which the authors deduct a similarly vague fifth for intermediate inputs ("based on the 1841 input-output table for England", we're assured) before adding a conservative 40% to what remains, arriving thereby at a per capita GDP equivalent to 1,077 litres of barley annually, which they then equate to 862 litres of wheat, 52% of English income in 1688 and hence $736 of the 1990 Geary-Khamis dollars used by Maddison.

The issue here isn't so much the final number, which is probably about as useful and relevant as any given that ancient Mesopotamians didn't use 1990 dollars or prices: rather, the method itself exposes the severe shortcomings of the whole approach. For as Foldvari & van Leeuwen observe, the figures imply "an exchange rate of 1.17 litre wheat per one G-K 1990 dollar". This works out at just over 1,100 notional international dollars of 1990 value for a tonne of wheat (and note that the English prices around which the calculation revolves are wholesale, not retail, while the Roman and Mesopotamian levels are computed by bulk rather than value).

The problem is that a tonne of wheat wasn't worth anything approaching $1,100 in 1990. Anywhere. In fact the crop in that year fetched only $135 on the international market. It's true that wheat prices were depressed in the latter part of 1990 following a bumper harvest in the US (where the price was as low as $96). But even at the higher price of 1989 the product was worth only $170 per tonne - rather more than its average of $160 over the whole of 1980-2010, a period that includes the record prices of 2007-08.

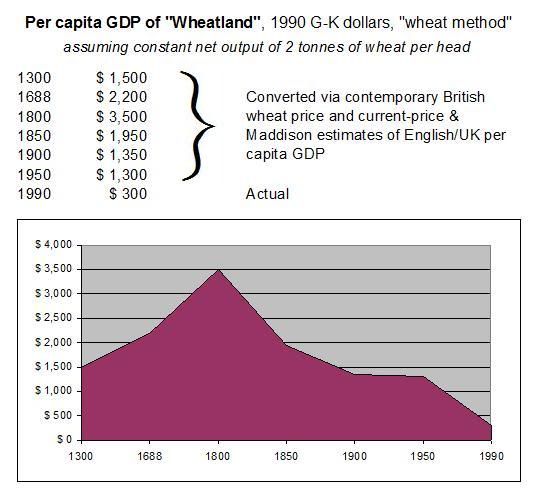

Imagine an economy which produced only two tonnes of wheat per head of population (net of seed and that part of the crop traded for other related inputs) and nothing else, trading its resulting healthy grain surplus with visiting foreign merchants for life's other necessities and occasional luxuries. In 1688 this notional territory would enjoy a world-leading per capita GDP of 2,200 G-K 1990 dollars according to the Maddison-LCM-FvL calculations. In the real 1990, however, its inhabitants would earn around $270, in 1989 $340 - below Maddison's subsistence allowance and the dollar-a-day of purchasing power often used to denote crushing poverty, and below even the $434 for Chad, the country at the bottom of Maddison's ranking.

The way current GDP estimates in Geary-Khamis dollars are computed means that the result offers no guide to the value of any product or sector within the economy, nor is it meant to. And the consequent uncertainties multiply as current incomes are projected into the past on the basis of assumed national economic growth rates. But in the aggregate, the final totals are assumed to bear some relation to reality across time and place. The England-Rome-Mesopotamia conjecture shows that they may not.

No comments:

Post a Comment